摘要: 表面等离子共振(Surface Plasmon Resonance,SPR)技术是一种通过检测薄金属膜(通常是金膜)表面附近局部折射率的变化来进行灵敏、实时、原位动态表面事件分析的生物物理技术[104]。在生命科学研究领域,SPR技术以其高灵敏度、无标记的显著优点被广泛运用于从基础研究到早期药物研发的各阶段,是研究生物分子间相互作用的有力工具。鉴于该技术对于科学研究的重要性,本文收集了上百篇顶尖研究论文,通过分析统计研究论文中SPR技术运用的各细节,为广大科研工作者提供了从SPR实验方案设计到论文数据呈现等多方面有用的参考。希望该文能够帮助从事SPR技术研究学者获得重复性好、可靠的研究数据,加快推动相应研究进程。

关键词: 表面等离子共振技术, 生物分子间相互作用, SPR技术运用统计

SPR技术发展背景

表面等离子共振(SPR)技术起源于20世纪初,作为一种新型光学检测手段,其理论基础最早由Wood于1902年在光学实验中观察并简单记录了SPR现象。然而,直至1941年,Fano才对这一现象进行了系统性解释,为SPR研究奠定了理论基础。在随后的近三十年中,SPR技术未见实质性发展,也未被应用于实践。直至1971年,Kretschmann等人提出了经典的SPR传感器结构,为SPR技术的实验应用提供了技术框架。1983年,Liedberg等人首次成功利用SPR技术实现了抗原-抗体反应的检测,为该技术在生物分子相互作用研究中的应用开辟了新方向。随后,1987年Knoll等人开始基于SPR技术开展成像设施的研究,进一步推动了其功能拓展。1990年,Pharmacia Biosensor AB公司(现为Cytiva公司)推出首台商业化SPR仪器,标志着SPR技术进入广泛应用的新时代。SPR技术是基于光与金属膜表面电子振荡相互作用的原理。当光在棱镜与金属膜界面发生全反射时,会在光疏介质中产生一束伴随消逝波的电磁场,同时在金属膜界面激发表面等离子波。当入射光的波矢与表面等离子波的波矢匹配时,产生共振现象,导致反射光强度显著降低,能量从光子转移至表面等离子波。此时,在反射光强度曲线中会观察到一个明显的最低点,该点对应的入射角即为SPR角,而对应的波长被称为共振波长。SPR角的变化与金属膜表面折射率的变化密切相关,而折射率的变化又与金属膜表面结合的分子质量成正比。因此,通过监测SPR角随时间的动态变化,可以实时获取分子间相互作用的特异性信号,从而实现分子识别与定量分析。

在利用SPR技术进行生物分子间结合检测时,在传感器芯片表面,通常会固定一种被称为配体的目标分子(如抗体、受体等蛋白),当另一种分析物分子(如抗原、小分子等)在溶液中流动并与固定的目标分子发生相互作用时,会引起芯片表面折射率的变化。这种折射率的改变会进一步导致共振角的偏移。通过检测共振角的变化来获取生物分子相互作用的特异信号。因此,SPR技术具有高灵敏度、无标记地实时测量动力学数据等优点。

借助表面等离子共振技术优势,其可用来检测各种成分,如掺假物、抗生素、生物分子、转基因食品、农药、杀虫剂、除草剂、微生物和食品中的微生物毒素。因而,SPR技术被广泛运用于生命科学的基础研究、药物研发、医学临床诊断、环境监测以及法医鉴定、食品安全监测等多个领域[103]。

1997年,美国食品药品监督管理局FDA批准了第一个使用SPR技术开发的抗IL-2受体人源化单克隆抗体。截至2024年,超过85%FDA获批上市的抗体药物在其研发、临床实验甚至生产中都使用到了SPR技术完成相应的工作内容。目前已有超65,000篇发表的研究论文中使用了该技术。SPR技术已成为基础科研以及生物医药领域必不可少的攻坚利器。但另一方面,SPR技术的使用成本不容忽视。鉴于此,为了让广大科研工作者在进行SPR实验时顺利获得可靠的实验结果,本文从Nature、Science和Cell这三本具有显著影响力的学术期刊杂志中收集了近三年来生命科学研究领域涉及SPR技术的102篇学术论文,并对每篇文章中SPR实验的相关细节进行了统计,浓缩出的SPR技术使用细节信息供有需求的学者们参考。

102篇学术论文中SPR技术实验细节的统计分析结果

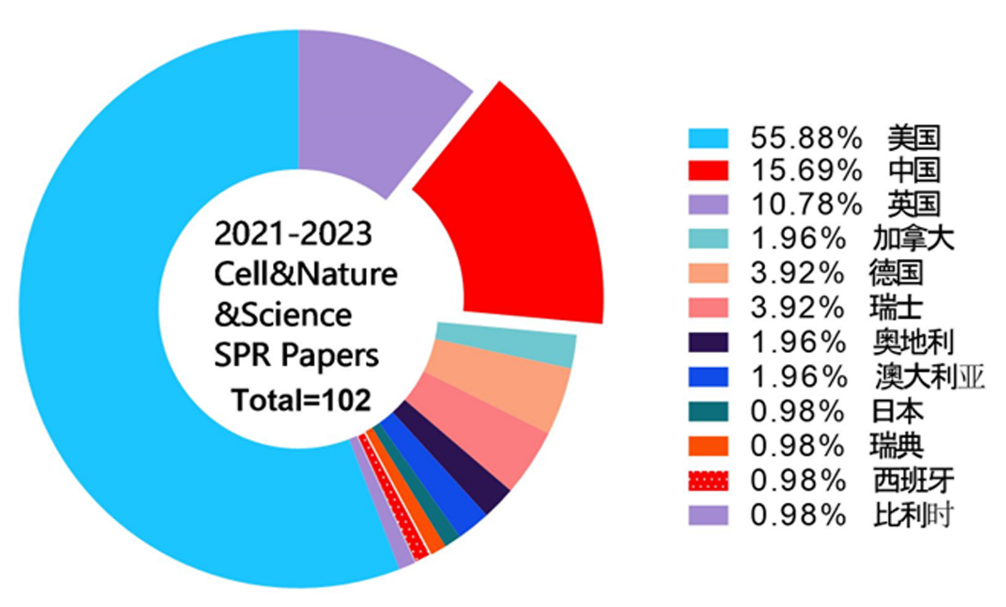

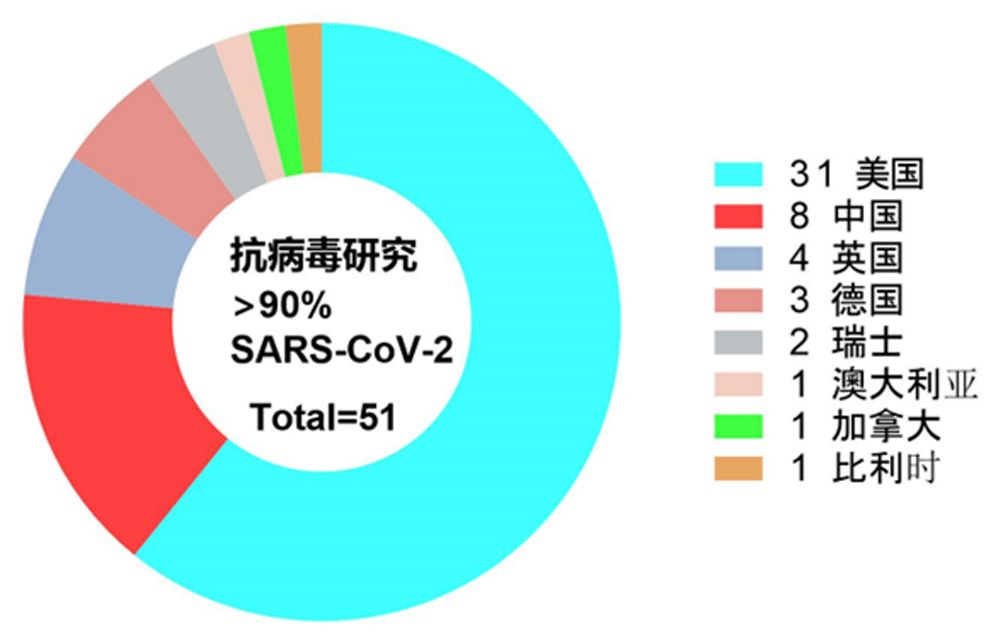

本文收集了自2021年至2023年期间,发表在Nature、Science及Cell三种国际著名学术期刊中涉及到SPR技术使用的102篇聚焦生命科学研究学术论文。其中2021年36篇,2022年43篇,2023年锐减到23篇。涵盖Cell 杂志33篇论文,Nature杂志40篇以及Science杂志29篇论文。其中有96篇文章来自学术界,6篇文章源自生物公司。如图1所示,102篇研究论文中使用SPR技术最频繁的是美国学者,其次是中国学者。有一半的论文使用SPR技术进行抗病毒研究,例如病毒抗原、抗体亲和力测定,或者针对病毒抗原开展的抗体筛选。由于新型冠状病毒造成的全球疫情缘故,在这些抗病毒研究中超过90%聚焦于SARS-CoV-2病毒的抗体研究。在抗新冠病毒研究中,美国学者使用SPR技术发表的研究论文数量占比约60%,远高于中国学者,该统计结果如图2所示。

图1 所收集的研究论文国家来源统计

图2 利用SPR技术开展抗SARS-CoV-2新型冠状病毒研究的国家来源统计

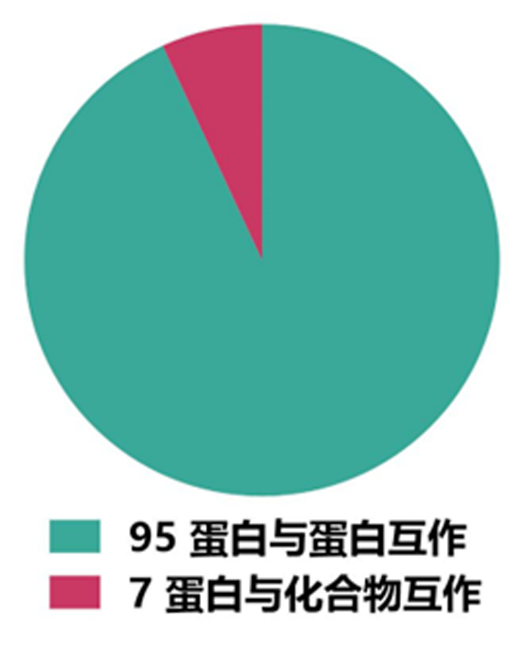

从SPR技术研究对象来看,所收集的研究论文绝大多数是针对蛋白与蛋白互作的特性研究,只有7篇论文利用SPR技术研究蛋白与小分子互作的特性(图3)。这个统计结果一方面可以反映出SPR技术优势,另一方面也可能是新冠疫情影响导致的结果。

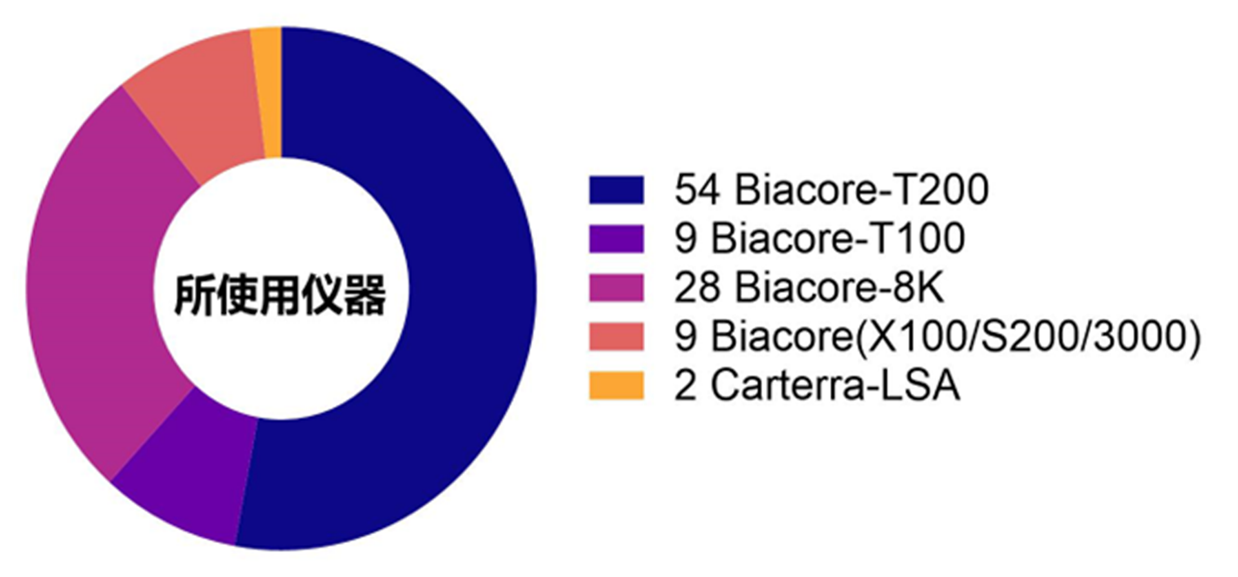

通过统计研究论文中所使用的SPR技术仪器类型可以看到,使用频率最高的是Biacore T200机型,其次是具备高通量性能的Biacore 8K机型,之后是Biacore T100 (Biacore T200的前身), 以及Biacore X100、Biacore S200、Biacore 3000。该统计结果一定程度上反映了仪器的性能稳定性,以及仪器操作灵活便捷程度。当需要进行更高通量、更大规模的抗体筛选以及抗原、抗体结合解离特性表征时可采用Carterra-LSA仪器(图4)。

图3 所收集研究论文中SPR技术研究对象统计结果

图4 所收集研究论文中使用的SPR技术仪器统计结果

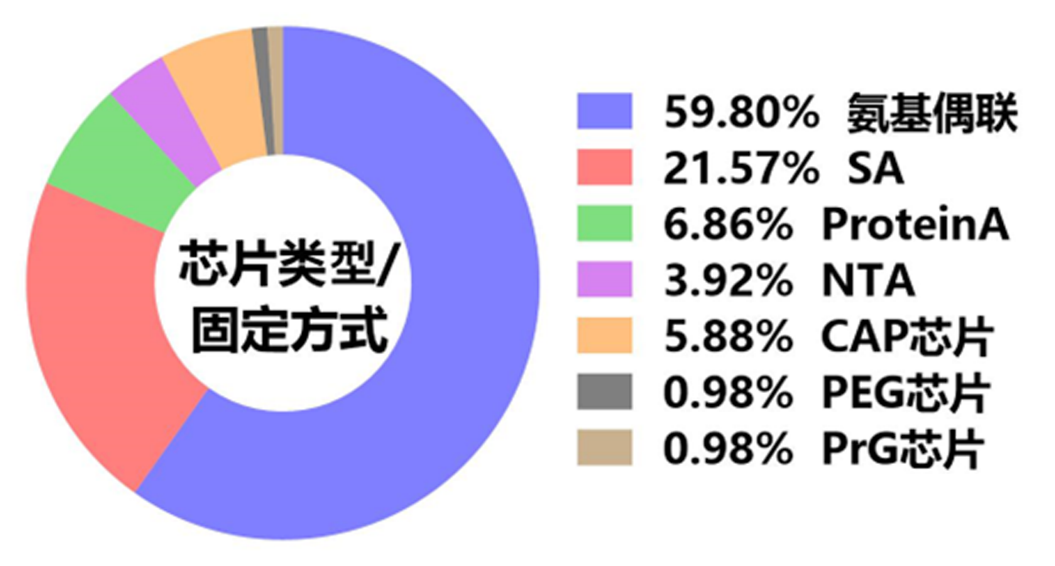

在SPR实验细节方面,超过半数的研究通过氨基偶联方式来固定配体蛋白,61项通过氨基偶联法固定配体的实验中,56项实验采用了CM5芯片,2项实验使用了CM7芯片,另有2项实验使用了C1芯片,1项实验采用了C4芯片。有大约22%的研究是通过链霉亲和素SA蛋白与生物素标记的配体相连方式固定(图5)。不足百分之二十的研究在实验中分别采用了PrA芯片、CAP芯片等捕获方式来固定配体。在SPR实验中,氨基偶联通过共价反应将配体共价结合在传感芯片表面;SA芯片则利用链霉亲和素SA蛋白与生物素高达10-15M的牢固亲和力来固定相应配体。这两种固定配体方法可使实验者获得相对更稳定的基线,从图五统计结果来看,这两种配体固定方法的使用频率也明显高于其他类型芯片所对应的捕获型配体固定方法。

图5 SPR实验中所使用芯片以及配体固定方式统计结果

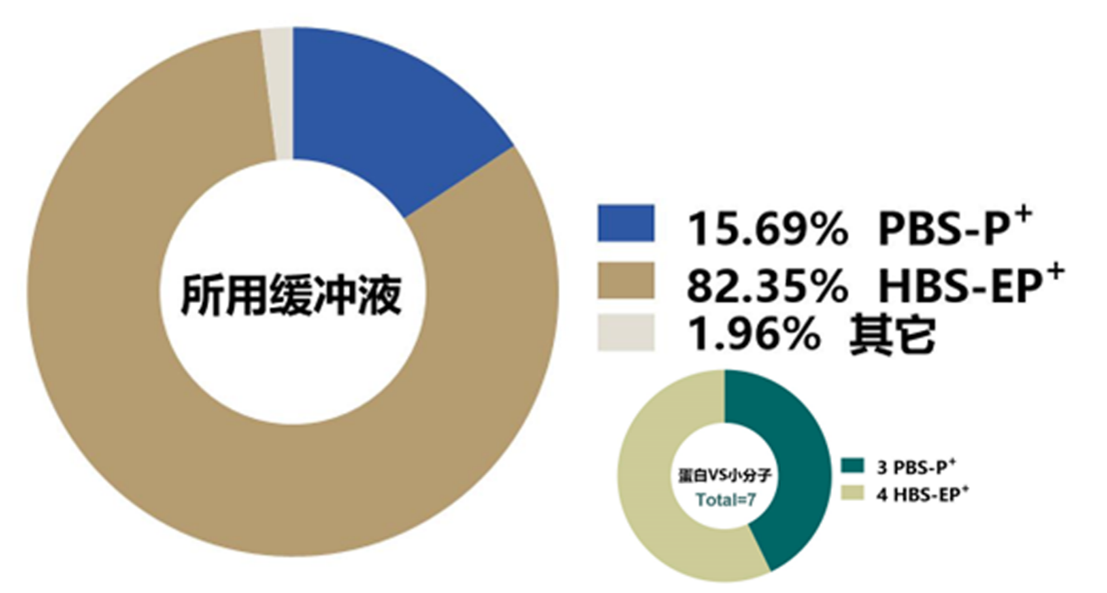

SPR实验中选择合适的运行缓冲液往往有助于产生可靠的检测结果。相反,如果运行缓冲液选择不当,则有可能导致实验失败。通过统计,我们发现超过80%的研究论文中SPR实验运行缓冲液为HBS-EP+,约16%的SPR实验运行缓冲液为PBS-P+。在前面所述的7项研究蛋白与小分子亲和特征的SPR实验中,有4例使用了HBS-EP+运行缓冲液,3例使用了PBS-P+运行缓冲液(图6)。该统计结果提示,在进行蛋白与蛋白互作亲和力检测时,HBS-EP+可以作为实验所需运行缓冲液的首选;而针对蛋白与小分子的互作特征研究而言,两种缓冲液都可考虑作为运行缓冲液。

图6 SPR实验中所使用运行缓冲液类型统计结果

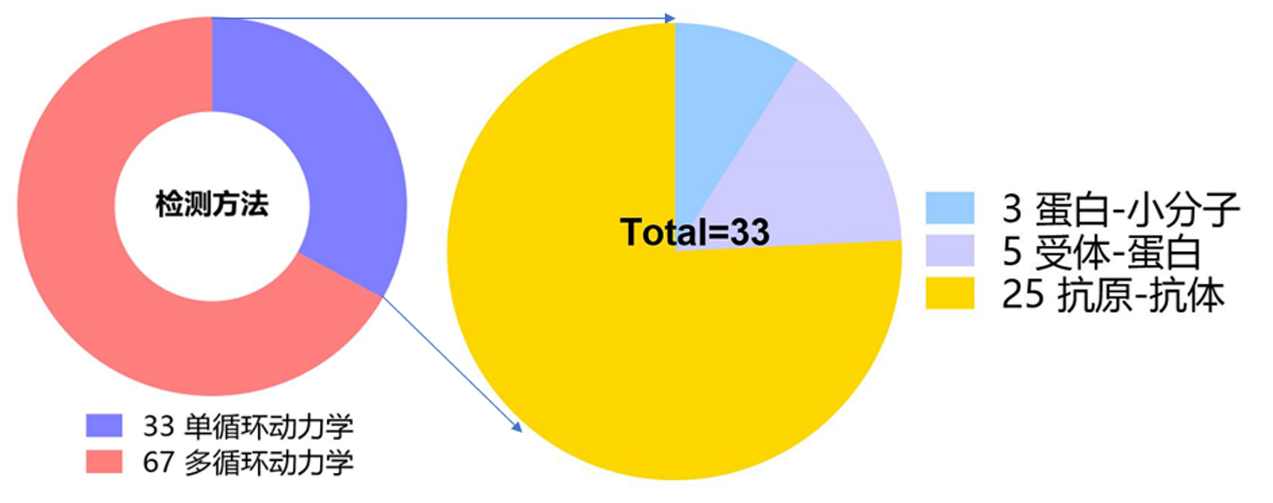

在利用SPR技术进行生物分子间结合亲和力检测的时候,分析物进样可以采取单循环(single-cycle)模式或者多循环(Multi-cycle)模式。单循环动力学检测方法适用于快速筛选和初步动力学参数的估计,而多循环动力学检测方法则可更精准地检测分子间互作的动力学参数。当分析物样品量有限,或者分析物与配体结合后的解离速度非常慢时,可以考虑采用单循环动力学方法来实验。如图7所示,在收集的研究论文中,有33例SPR实验采用了单循环动力学方法来检测分析参数,67例SPR实验采用了多循环动力学检测方法来获得动力学参数。在33例采用单循环动力学模式的研究对象中,四分之三为针对抗原抗体亲和力表征,5例为受体与蛋白亲和力表征,3例为蛋白与小分子互作检测。这一统计结果提示在进行抗原与抗体亲和力表征SPR实验中,可通过单循环动力学检测方法来开展快速筛选以及初步动力学参数检测。

图7 SPR实验中检测方法统计结果

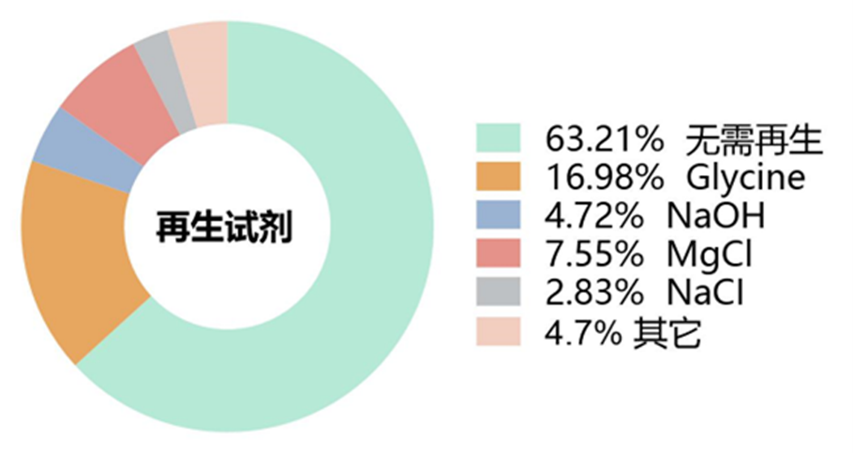

在多循环动力学检测过程中,通常会涉及到再生试剂的使用。再生试剂的使用是为了在每次分析循环后从传感芯片表面去除结合的残留分析物,以便为下一个分析循环做准备,同时也可充分保证下一个分析循环的基线平稳。但常用的再生试剂通常是强酸、强碱以及高浓度盐溶液等,这些再生试剂因条件剧烈,其在芯片再生过程中容易造成固定在芯片表面的配体蛋白失活,最终导致实验失败。因此,替代再生步骤的温和处理方案是不使用再生试剂,仅通过长时间的运行缓冲液的冲洗来尽可能去除上一个分析循环中残留的分析物。从本文统计图8来看,约64%的SPR实验没有使用再生试剂,这其中除33例因采用单循环动力学实验而无需再生过程以外,有近一半的多循环动力学检测实验并没有使用再生试剂。再生试剂中使用频率最高的是不同pH值甘氨酸-盐酸溶液例如:10 mM Glycine-HCl (pH1, pH1.5, pH2.0, pH2.5, pH3.0);其次是不同浓度的氯化镁例如:2 M MgCl2, 3 M MgCl2, 4 M MgCl2;以及不同浓度的强碱NaOH例如:5 mM NaOH, 25 mM NaOH, 50 mM NaOH;此外,还有SPR实验中使用500 mM NaCl, 1 M NaCl, 0.35 M EDTA and 0.1 M NaOH, 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0) containing 1 M NaCl, Phosphoric acid 1.7%, 50% isopropanol以及1 M NaCl and 50 mM NaOH来进行再生。

图8 SPR实验中再生试剂使用情况统计结果

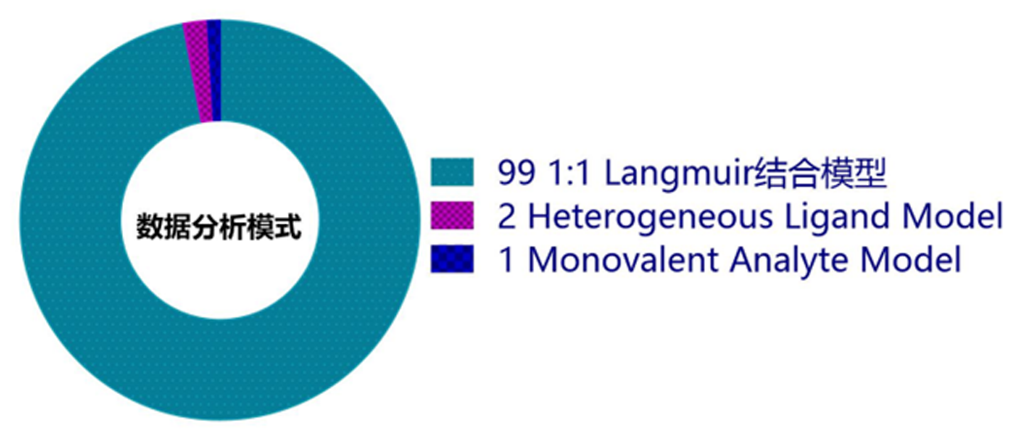

在统计的研究论文中,几乎所有SPR实验数据分析模式都遵循了1:1 Langmuir结合模型来进行亲和力参数拟合(图9)。只有2例研究采用了Heterogeneous Ligand模型这样的多位点结合模型,1例采用了Monovalent Analyte模型。

图9 SPR实验中数据分析模式统计结果

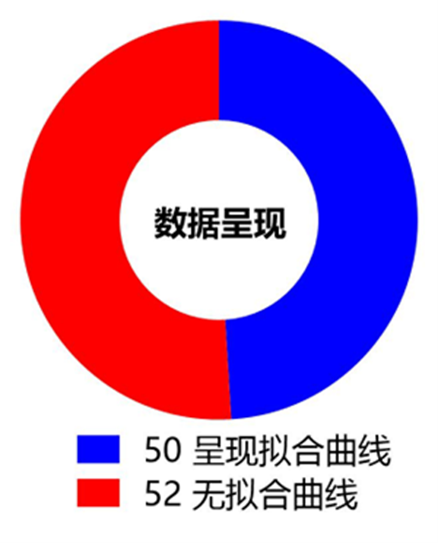

在SPR实验数据分析时的拟合曲线可以获得结合速率常数(Ka)、解离速率常数(Kd)和亲和力(KD)这些描述了分子间的动力学特性和结合强度的参数,从而更好地理解实验结果。通过分析拟合曲线与原始传感曲线的紧密或是离散程度以及Chi2值,可以判断拟合的可靠程度。如图10所示,所有统计的研究论文中,有超过一半的SPR实验结果没有呈现拟合曲线,由此说明在发表文章时,SPR实验数据传感图中呈现拟合曲线并不是必须的,但推荐使用。

图10 SPR实验中数据呈现方式统计结果

结语

本文通过分析顶尖学术期刊收集的102篇研究论文中SPR实验各细节,从研究团队来源、研究对象到实验所用分析机型、配体固定方式、缓冲液、再生条件、拟合方式、结果呈现方式,综述了SPR技术运用概况及其实验注意要点。帮助读者对SPR技术在生命科学研究领域的运用有相对更全面的了解。为了方便读者能够获取更多的SPR实验细节,作者在文末参考文献处添加所有102篇调研的研究论文信息。

致谢

作者感谢Cytiva公司孔伟博士帮忙收集大量的SPR技术相关研究论文,以及在SPR实验时所提供的卓有成效的技术支持。

参考文献

- MODHIRAN N, SONG H, LIU L, et al. A broadly protective antibody that targets the flavivirus NS1 protein. Science, 2021, 371(6525): 190–194. DOI:10.1126/science.abb9425.

- AUGUSTO D G, MURDOLO L D, CHATZILEONTIADOU D S M, et al. A common allele of HLA is associated with asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature, 2023, 620(7972): 128–136. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-06331-x.

- MOMONT C, DANG H V, ZATTA F, et al. A pan-influenza antibody inhibiting neuraminidase via receptor mimicry. Nature, 2023, 618(7965): 590–597. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-06136-y.

- SHILTS J, SEVERIN Y, GALAWAY F, et al. A physical wiring diagram for the human immune system. Nature, 2022, 608(7922): 397–404. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05028-x.

- GONG G Q, BILANGES B, ALLSOP B, et al. A small-molecule PI3Kα activator for cardioprotection and neuroregeneration. Nature, 2023, 618(7963): 159–168. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-05972–2.

- WANG Q, IKETANI S, LI Z, et al. Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants. Cell, 2023, 186(2): 279–286.e8. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.018.

- MO F, YU Z, LI P, et al. An engineered IL-2 partial agonist promotes CD8+ T cell stemness. Nature, 2021, 597(7877): 544–548. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03861–0.

- AUTHEMAN D, CROSNIER C, CLARE S, et al. An invariant Trypanosoma vivax vaccine antigen induces protective immunity. Nature, 2021, 595(7865): 96–100. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03597-x.

- TUEKPRAKHON A, NUTALAI R, DIJOKAITE-GURALIUC A, et al. Antibody escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 from vaccine and BA.1 serum. Cell, 2022, 185(14): 2422–2433.e13. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.005.

- WANG Q, GUO Y, IKETANI S, et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature, 2022, 608(7923): 603–608. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05053-w.

- PARK Y J, MARCO A D, STARR T N, et al. Antibody-mediated broad sarbecovirus neutralization through ACE2 molecular mimicry[J].

- WANG Q, GUO Y, LIU L, et al. Antigenicity and receptor affinity of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 spike. Nature, 2023, 624(7992): 639–644. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-06750-w.

- TSIANTOULAS D, ESLAMI M, OBERMAYER G, et al. APRIL limits atherosclerosis by binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Nature, 2021, 597(7874): 92–96. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03818–3.

- YANG X, GARNER L I, ZVYAGIN I V, et al. Autoimmunity-associated T cell receptors recognize HLA-B*27-bound peptides. Nature, 2022, 612(7941): 771–777. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022–05501-7.

- SCHEID J F, BARNES C O, ERASLAN B, et al. B cell genomics behind cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variants and SARS-CoV. Cell, 2021, 184(12): 3205–3221.e24. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.032.

- CAO Y, YISIMAYI A, JIAN F, et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron infection. Nature, 2022, 608(7923): 593–602. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-04980-y.

- LIU K, PAN X, LI L, et al. Binding and molecular basis of the bat coronavirus RaTG13 virus to ACE2 in humans and other species. Cell, 2021, 184(13): 3438–3451.e10. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.031.

- DE GASPARO R, PEDOTTI M, SIMONELLI L, et al. Bispecific IgG neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 variants and prevents escape in mice. Nature, 2021, 593(7859): 424–428. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03461-y.

- VOGEL A B, KANEVSKY I, CHE Y, et al. BNT162b vaccines protect rhesus macaques from SARS-CoV-2. Nature, 2021, 592(7853): 283–289. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03275-y.

- RAPPAZZO C G, TSE L V, KAKU C I, et al. Broad and potent activity against SARS-like viruses by an engineered human monoclonal antibody. Science, 2021, 371(6531): 823–829. DOI:10.1126/science.abf4830.

- PINTO D, SAUER M M, CZUDNOCHOWSKI N, et al. Broad betacoronavirus neutralization by a stem helix–specific human antibody. Science, 2021, 373(6559): 1109–1116. DOI:10.1126/science.abj3321.

- TORTORICI M A, CZUDNOCHOWSKI N, STARR T N, et al. Broad sarbecovirus neutralization by a human monoclonal antibody. Nature, 2021, 597(7874): 103–108. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03817–4.

- DACON C, TUCKER C, PENG L, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies target the coronavirus fusion peptide[J].

- ZAREIE P, SZETO C, FARENC C, et al. Canonical T cell receptor docking on peptide–MHC is essential for T cell signaling. Science, 2021, 372(6546): eabe9124. DOI:10.1126/science.abe9124.

- THOMSON E C, ROSEN L E, SHEPHERD J G, et al. Circulating SARS-CoV-2 spike N439K variants maintain fitness while evading antibody-mediated immunity. Cell, 2021, 184(5): 1171–1187.e20. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.037.

- HOI D M, JUNKER S, JUNK L, et al. Clp-targeting BacPROTACs impair mycobacterial proteostasis and survival. Cell, 2023, 186(10): 2176–2192.e22. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2023.04.009.

- RAO S P S, GOULD M K, NOESKE J, et al. Cyanotriazoles are selective topoisomerase II poisons that rapidly cure trypanosome infections. Science, 2023, 380(6652): 1349–1356. DOI:10.1126/science.adh0614.

- GAINZA P, WEHRLE S, VAN HALL-BEAUVAIS A, et al. De novo design of protein interactions with learned surface fingerprints. Nature, 2023, 617(7959): 176–184. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-05993-x.

- HUANG S K, PANDEY A, TRAN D P, et al. Delineating the conformational landscape of the adenosine A2A receptor during G protein coupling. Cell, 2021, 184(7): 1884–1894.e14. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.041.

- YANG A, JUDE K M, LAI B, et al. Deploying synthetic coevolution and machine learning to engineer protein-protein interactions. Science, 2023, 381(6656): eadh1720. DOI:10.1126/science.adh1720.

- ZHU Y, HART G W. Dual-specificity RNA aptamers enable manipulation of target-specific O-GlcNAcylation and unveil functions of O-GlcNAc on β-catenin. Cell, 2023, 186(2): 428–445.e27. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.016.

- GOBEIL S M C, JANOWSKA K, MCDOWELL S, et al. Effect of natural mutations of SARS-CoV-2 on spike structure, conformation, and antigenicity. Science, 2021, 373(6555): eabi6226. DOI:10.1126/science.abi6226.

- EICHEL K, UENAKA T, BELAPURKAR V, et al. Endocytosis in the axon initial segment maintains neuronal polarity. Nature, 2022, 609(7925): 128–135. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05074–5.

- YAMIN R, JONES A T, HOFFMANN H H, et al. Fc-engineered antibody therapeutics with improved anti-SARS-CoV-2 efficacy. Nature, 2021, 599(7885): 465–470. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-04017-w.

- HU C, LECHE C A, KIYATKIN A, et al. Glioblastoma mutations alter EGFR dimer structure to prevent ligand bias. Nature, 2022, 602(7897): 518–522. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-04393–3.

- AKKERMANS O, DELLOYE-BOURGEOIS C, PEREGRINA C, et al. GPC3-Unc5 receptor complex structure and role in cell migration. Cell, 2022, 185(21): 3931–3949.e26. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.025.

- PAIK D, YAO L, ZHANG Y, et al. Human gut bacteria produce ΤΗ17-modulating bile acid metabolites. Nature, 2022, 603(7903): 907–912. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-04480-z.

- ZHOU H, JI J, CHEN X, et al. Identification of novel bat coronaviruses sheds light on the evolutionary origins of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses. Cell, 2021, 184(17): 4380–4391.e14. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.008.

- LI Y, SHEN H, ZHANG R, et al. Immunoglobulin M perception by FcμR. Nature, 2023, 615(7954): 907–912. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-05835-w.

- PARK Y J, PINTO D, WALLS A C, et al. Imprinted antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages[J].

- LI D, EDWARDS R J, MANNE K, et al. In vitro and in vivo functions of SARS-CoV-2 infection-enhancing and neutralizing antibodies. Cell, 2021, 184(16): 4203–4219.e32. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.021.

- DAI W, ZHANG H, LUND H, et al. Intracellular tPA–PAI-1 interaction determines VLDL assembly in hepatocytes. Science, 2023, 381(6661): eadh5207. DOI:10.1126/science.adh5207.

- QIN F, LI B, WANG H, et al. Linking chromatin acylation mark-defined proteome and genome in living cells. Cell, 2023, 186(5): 1066–1085.e36. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.007.

- LEE J H, SUTTON H J, COTTRELL C A, et al. Long-primed germinal centres with enduring affinity maturation and clonal migration. Nature, 2022, 609(7929): 998–1004. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05216–9.

- MA T, TIAN X, ZHANG B, et al. Low-dose metformin targets the lysosomal AMPK pathway through PEN2. Nature, 2022, 603(7899): 159–165. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-04431–8.

- JANETZKO J, KISE R, BARSI-RHYNE B, et al. Membrane phosphoinositides regulate GPCR-β-arrestin complex assembly and dynamics. Cell, 2022, 185(24): 4560–4573.e19. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.10.018.

- MCCALLUM M, WALLS A C, SPROUSE K R, et al. Molecular basis of immune evasion by the Delta and Kappa SARS-CoV-2 variants[J].

- GAGNE M, MOLIVA J I, FOULDS K E, et al. mRNA-1273 or mRNA-Omicron boost in vaccinated macaques elicits similar B cell expansion, neutralizing responses, and protection from Omicron. Cell, 2022, 185(9): 1556–1571.e18. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.038.

- MCCALLUM M, DE MARCO A, LEMPP F A, et al. N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell, 2021, 184(9): 2332–2347.e16. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.028.

- ADDETIA A, PICCOLI L, CASE J B, et al. Neutralization, effector function and immune imprinting of Omicron variants. Nature, 2023, 621(7979): 592–601. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-06487–6.

- SAUNDERS K O, LEE E, PARKS R, et al. Neutralizing antibody vaccine for pandemic and pre-emergent coronaviruses. Nature, 2021, 594(7864): 553–559. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03594–0.

- LIU K H, LIU M, LIN Z, et al. NIN-like protein 7 transcription factor is a plant nitrate sensor. Science, 2022, 377(6613): 1419–1425. DOI:10.1126/science.add1104.

- BOWEN J E, ADDETIA A, DANG H V, et al. Omicron spike function and neutralizing activity elicited by a comprehensive panel of vaccines. Science, 2022, 377(6608): 890–894. DOI:10.1126/science.abq0203.

- WILSON S C, CAVENEY N A, YEN M, et al. Organizing structural principles of the IL-17 ligand–receptor axis. Nature, 2022, 609(7927): 622–629. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05116-y.

- KIM D, HERDEIS L, RUDOLPH D, et al. Pan-KRAS inhibitor disables oncogenic signalling and tumour growth. Nature, 2023, 619(7968): 160–166. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-06123–3.

- ROLLENSKE T, BURKHALTER S, MUERNER L, et al. Parallelism of intestinal secretory IgA shapes functional microbial fitness. Nature, 2021, 598(7882): 657–661. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03973–7.

- BUCHANAN C J, GAUNT B, HARRISON P J, et al. Pathogen-sugar interactions revealed by universal saturation transfer analysis. Science, 2022, 377(6604): eabm3125. DOI:10.1126/science.abm3125.

- LIU Z, HOU S, RODRIGUES O, et al. Phytocytokine signalling reopens stomata in plant immunity and water loss. Nature, 2022, 605(7909): 332–339. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-04684–3.

- NUTALAI R, ZHOU D, TUEKPRAKHON A, et al. Potent cross-reactive antibodies following Omicron breakthrough in vaccinees. Cell, 2022, 185(12): 2116–2131.e18. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.05.014.

- CORBETT K S, GAGNE M, WAGNER D A, et al. Protection against SARS-CoV-2 Beta variant in mRNA-1273 vaccine–boosted nonhuman primates. Science, 2021, 374(6573): 1343–1353. DOI:10.1126/science.abl8912.

- GAGNE M, CORBETT K S, FLYNN B J, et al. Protection from SARS-CoV-2 Delta one year after mRNA-1273 vaccination in rhesus macaques coincides with anamnestic antibody response in the lung. Cell, 2022, 185(1): 113–130.e15. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.002.

- GAGNE M, CORBETT K S, FLYNN B J, et al. Protection from SARS-CoV-2 Delta one year after mRNA-1273 vaccination in rhesus macaques coincides with anamnestic antibody response in the lung. Cell, 2022, 185(1): 113–130.e15. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.002.

- XU K, GAO P, LIU S, et al. Protective prototype-Beta and Delta-Omicron chimeric RBD-dimer vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Cell, 2022, 185(13): 2265–2278.e14. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.029.

- HAN P, LI L, LIU S, et al. Receptor binding and complex structures of human ACE2 to spike RBD from omicron and delta SARS-CoV-2. Cell, 2022, 185(4): 630–640.e10. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.001.

- KATO H, NEMOTO K, SHIMIZU M, et al. Recognition of pathogen-derived sphingolipids in Arabidopsis. Science, 2022, 376(6595): 857–860. DOI:10.1126/science.abn0650.

- YU X, ORR C M, CHAN H T C, et al. Reducing affinity as a strategy to boost immunomodulatory antibody agonism. Nature, 2023, 614(7948): 539–547. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05673–2.

- YISIMAYI A, SONG W, WANG J, et al. Repeated Omicron exposures override ancestral SARS-CoV-2 immune imprinting. Nature, 2024, 625(7993): 148–156. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-06753–7.

- LOGAN T, SIMON M J, RANA A, et al. Rescue of a lysosomal storage disorder caused by Grn loss of function with a brain penetrant progranulin biologic. Cell, 2021, 184(18): 4651–4668.e25. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.002.

- WANG J, MIAO Y, WICKLEIN R, et al. RTN4/NoGo-receptor binding to BAI adhesion-GPCRs regulates neuronal development. Cell, 2021, 184(24): 5869–5885.e25. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.10.016.

- REINCKE S M, YUAN M, KORNAU H C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Beta variant infection elicits potent lineage-specific and cross-reactive antibodies[J].

- MCCALLUM M, BASSI J, DE MARCO A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 immune evasion by the B.1.427/B.1.429 variant of concern. Science, 2021, 373(6555): 648–654. DOI:10.1126/science.abi7994.

- MANNAR D, SAVILLE J W, ZHU X, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Antibody evasion and cryo-EM structure of spike protein–ACE2 complex. Science, 2022, 375(6582): 760–764. DOI:10.1126/science.abn7760.

- DEJNIRATTISAI W, HUO J, ZHOU D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-B.1.1.529 leads to widespread escape from neutralizing antibody responses. Cell, 2022, 185(3): 467–484.e15. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.046.

- STARR T N, CZUDNOCHOWSKI N, LIU Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies that maximize breadth and resistance to escape. Nature, 2021, 597(7874): 97–102. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03807–6.

- WANG J, LISANZA S, JUERGENS D, et al. Scaffolding protein functional sites using deep learning[J].

- MARKLUND E, MAO G, YUAN J, et al. Sequence specificity in DNA binding is mainly governed by association. Science, 2022, 375(6579): 442–445. DOI:10.1126/science.abg7427.

- ROBINSON R A, GRIFFITHS S C, VAN DE HAAR L L, et al. Simultaneous binding of Guidance Cues NET1 and RGM blocks extracellular NEO1 signaling. Cell, 2021, 184(8): 2103–2120.e31. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.045.

- CUI Z, LIU P, WANG N, et al. Structural and functional characterizations of infectivity and immune evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Cell, 2022, 185(5): 860–871.e13. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.019.

- NABEL K G, CLARK S A, SHANKAR S, et al. Structural basis for continued antibody evasion by the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain. Science, 2022, 375(6578): eabl6251. DOI:10.1126/science.abl6251.

- GLASSMAN C R, MATHIHARAN Y K, JUDE K M, et al. Structural basis for IL-12 and IL-23 receptor sharing reveals a gateway for shaping actions on T versus NK cells. Cell, 2021, 184(4): 983–999.e24. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.018.

- LIAU N P D, JOHNSON M C, IZADI S, et al. Structural basis for SHOC2 modulation of RAS signalling. Nature, 2022, 609(7926): 400–407. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-04838–3.

- LI L, LIAO H, MENG Y, et al. Structural basis of human ACE2 higher binding affinity to currently circulating Omicron SARS-CoV-2 sub-variants BA.2 and BA.1.1. Cell, 2022, 185(16): 2952–2960.e10. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.023.

- MCCALLUM M, CZUDNOCHOWSKI N, ROSEN L E, et al. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron immune evasion and receptor engagement[J].

- ASARNOW D, WANG B, LEE W H, et al. Structural insight into SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and modulation of syncytia. Cell, 2021, 184(12): 3192–3204.e16. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.033.

- YANG Z, XIA J, HONG J, et al. Structural insights into auxin recognition and efflux by Arabidopsis PIN1. Nature, 2022, 609(7927): 611–615. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05143–9.

- RAWAL Y, JIA L, MEIR A, et al. Structural insights into BCDX2 complex function in homologous recombination. Nature, 2023, 619(7970): 640–649. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-06219-w.

- ZHONG X, ZENG H, ZHOU Z, et al. Structural mechanisms for regulation of GSDMB pore-forming activity. Nature, 2023, 616(7957): 598–605. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-05872–5.

- HAUSEMAN Z J, FODOR M, DHEMBI A, et al. Structure of the MRAS–SHOC2–PP1C phosphatase complex. Nature, 2022, 609(7926): 416–423. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05086–1.

- HOCHHEISER I V, PILSL M, HAGELUEKEN G, et al. Structure of the NLRP3 decamer bound to the cytokine release inhibitor CRID3. Nature, 2022, 604(7904): 184–189. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-04467-w.

- TSUTSUMI N, MASOUMI Z, JAMES S C, et al. Structure of the thrombopoietin-MPL receptor complex is a blueprint for biasing hematopoiesis. Cell, 2023, 186(19): 4189–4203.e22. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2023.07.037.

- BASORE K, MA H, KAFAI N M, et al. Structure of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in complex with the LDLRAD3 receptor. Nature, 2021, 598(7882): 672–676. DOI:10.1038/s41586–021-03963–9.

- SAXTON R A, TSUTSUMI N, SU L L, et al. Structure-based decoupling of the pro- and anti-inflammatory functions of interleukin-10. Science, 2021, 371(6535): eabc8433. DOI:10.1126/science.abc8433.

- KOENIG P A, DAS H, LIU H, et al. Structure-guided multivalent nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 infection and suppress mutational escape. Science, 2021, 371(6530): eabe6230. DOI:10.1126/science.abe6230.

- SU N, ZHU A, TAO X, et al. Structures and mechanisms of the Arabidopsis auxin transporter PIN3. Nature, 2022, 609(7927): 616–621. DOI:10.1038/s41586–022-05142-w.

- BEENKEN A, CERUTTI G, BRASCH J, et al. Structures of LRP2 reveal a molecular machine for endocytosis. Cell, 2023, 186(4): 821–836.e13. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.016.

- DEJNIRATTISAI W, ZHOU D, GINN H M, et al. The antigenic anatomy of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain. Cell, 2021, 184(8): 2183–2200.e22. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.032.

- BAGGEN J, JACQUEMYN M, PERSOONS L, et al. TMEM106B is a receptor mediating ACE2-independent SARS-CoV-2 cell entry. Cell, 2023, 186(16): 3427–3442.e22. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2023.06.005.

- ZHAO X, KOLAWOLE E M, CHAN W, et al. Tuning T cell receptor sensitivity through catch bond engineering. Science, 2022, 376(6589): eabl5282. DOI:10.1126/science.abl5282.

- WANG L, ZHOU T, ZHANG Y, et al. Ultrapotent antibodies against diverse and highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science, 2021, 373(6556): eabh1766. DOI:10.1126/science.abh1766.

- LEGGAT D J, COHEN K W, WILLIS J R, et al. Vaccination induces HIV broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in humans. Science, 2022, 378(6623): eadd6502. DOI:10.1126/science.add6502.

- GAO Y, HONG Y, HUANG L, et al. β2-microglobulin functions as an endogenous NMDAR antagonist to impair synaptic function. Cell, 2023, 186(5): 1026–1038.e20. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.021.

- PAREDES A, JUSTO-MÉNDEZ R, JIMÉNEZ-BLASCO D, et al. γ-Linolenic acid in maternal milk drives cardiac metabolic maturation. Nature, 2023, 618(7964): 365–373. DOI:10.1038/s41586–023-06068–7.

- Ravindran N, Kumar S, M Y, S R, C A M, Thirunavookarasu S N, C K S. Recent advances in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensors for food analysis: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63(8):1055–1077.

- Piliarik, M., Vaisocherová, H., Homola, J. (2009). Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensing. In: Rasooly, A., Herold, K.E. (eds) Biosensors and Biodetection. Methods in Molecular Biology™, vol 503. Humana Press.

Please login or register for free to view full text

View full text

Download PDF

Q&A

Copyright: © 2025 The Authors; exclusive licensee Bio-protocol LLC.

引用格式:刘伟, 兰姝珏, 陈铭. (2025). 2021年–2023年《Nature》&《Science》&《Cell》期刊论文中SPR技术应用统计. // Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Protocol eBook.

Bio-101: e1011026. DOI:

10.21769/BioProtoc.1011026.

How to cite:

How to cite: Liu, W., Lan, S. J. and Chen, H. (2025). Overview of the Application of SPR Technology in Nature, Science and Cell Journal Publications from 2021 to 2023. // Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Protocol eBook.

Bio-101: e1011026. DOI:

10.21769/BioProtoc.1011026.