- EN - English

- CN - 中文

Reproducible Emu-Based Workflow for High-Fidelity Soil and Plant Microbiome Profiling on HPC Clusters

基于 Emu 的可重复计算流程:在高性能计算集群上实现高保真土壤—植物微生物组解析

发布: 2026年01月20日第16卷第2期 DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5577 浏览次数: 442

评审: Migla MiskinyteYuhang Wang

Abstract

Accurate profiling of soil and root-associated bacterial communities is essential for understanding ecosystem functions and improving sustainable agricultural practices. Here, a comprehensive, modular workflow is presented for the analysis of full-length 16S rRNA gene amplicons generated with Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing. The protocol integrates four standardized steps: (i) quality assessment and filtering of raw reads with NanoPlot and NanoFilt, (ii) removal of plant organelle contamination using a curated Viridiplantae Kraken2 database, (iii) species-level taxonomic assignment with Emu, and (iv) downstream ecological analyses, including rarefaction, diversity metrics, and functional inference. Leveraging high-performance computing resources, the workflow enables parallel processing of large datasets, rigorous contamination control, and reproducible execution across environments. The pipeline’s efficiency is demonstrated on full-length 16S rRNA gene datasets from yellow pea rhizosphere and root samples, with high post-filter read retention and high-resolution community profiles. Automated SLURM scripts and detailed documentation are provided in a public GitHub repository (https://github.com/henrimdias/emu-microbiome-HPC; release v1.0.2, emu-pipeline-revised) and archived on Zenodo (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17764933).

Key features

• Implement rigorous quality control (QC) of raw 16S rRNA Nanopore reads and sequencing controls.

• Remove plant organelle contamination with a curated Kraken2 database.

• Perform high-resolution taxonomic assignment of full-length 16S rRNA reads using Emu.

• Integrate downstream statistical analyses, including rarefaction, PERMANOVA, and DESeq2 differential abundance.

• Conduct scalable microbiome diversity and functional analyses with FAPROTAX.

Keywords: Metabarcoding pipeline (宏条形码分析流程)Graphical overview

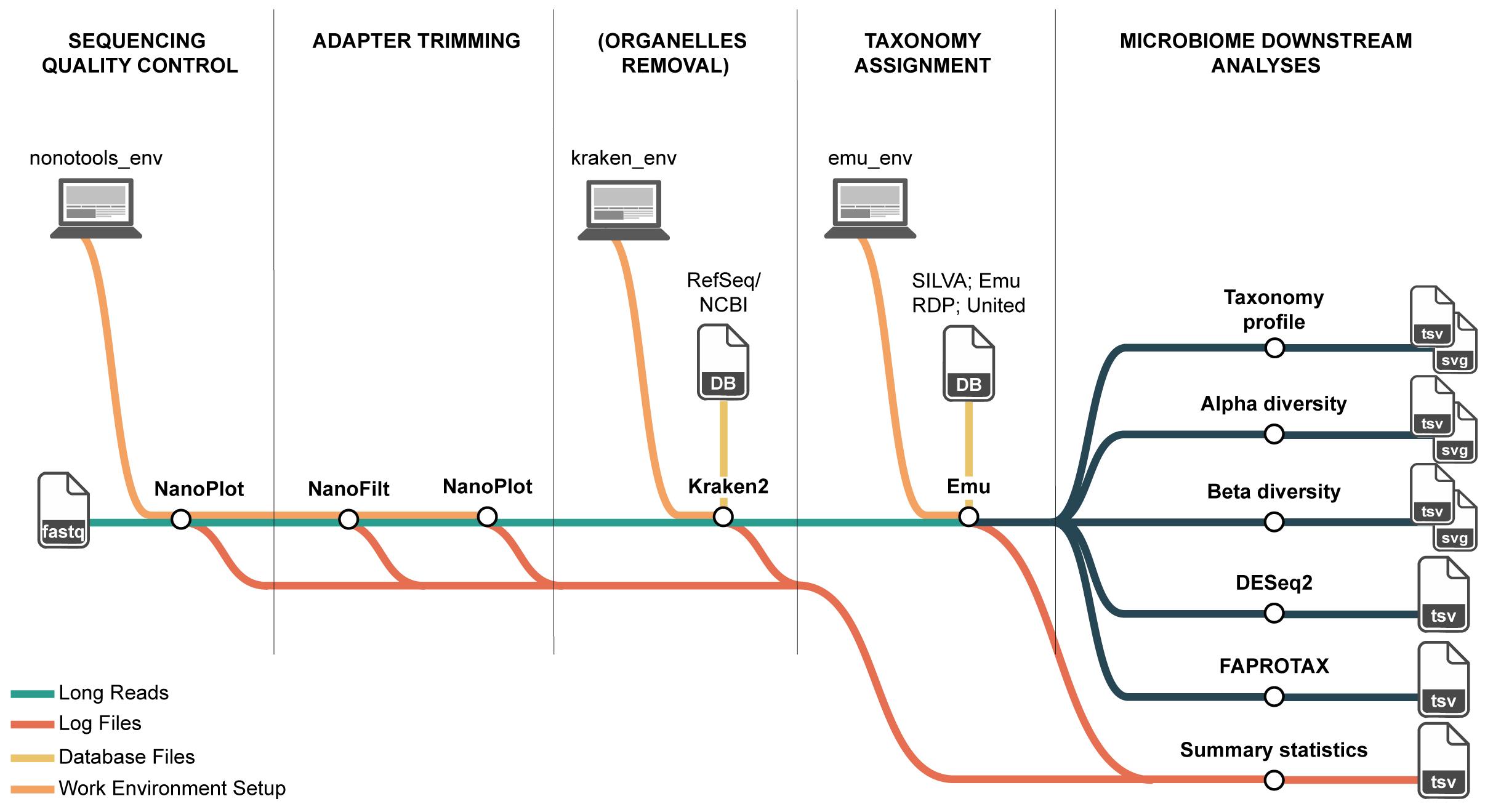

Overview of the long-read 16S rRNA microbiome workflow on high-performance computing (HPC). The pipeline comprises four steps and their primary inputs/outputs: (1) QC and filtering of Nanopore reads (NanoPlot, NanoFilt) producing per-sample QC reports and filtered FASTQ; (2) organelle removal with Kraken2 against a curated Viridiplantae (plastid and mitochondrial) database, yielding organelle-depleted FASTQ; (3) taxonomic assignment with Emu, generating four outputs, of which the species-level relative abundance table and the per-taxon read count table are used downstream; and (4) downstream ecological analyses that compute composition summaries and diversity metrics from these tables. Conda environments ensure reproducible tool execution on HPC, and log files from each step are retained for statistical summaries.

Background

Microbiomes play a central role in maintaining soil health and supporting plant development, influencing nutrient cycling, disease resistance, and overall ecosystem stability [1,2]. In both agricultural and natural systems, diverse microbial communities dominated by bacteria in soils and plant tissues are key drivers of biogeochemical processes such as carbon sequestration and nitrogen transformation [3]. Understanding the composition and functions of microbial communities provides a foundation for the development of new technologies, a guide for ecological management decisions, and the improvement of agricultural practices. However, accurate and consistent microbiome profiling remains a technical challenge, especially when dealing with complex environmental samples such as soil samples [4].

For bacterial community profiling, amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene remains a widely used, cost-effective approach for estimating community composition and diversity across environmental gradients and experimental manipulations [5]. In soils and plant compartments (rhizosphere, endosphere, and phyllosphere), where communities are both diverse and uneven, the ability to resolve taxa at finer ranks (e.g., species and, where possible, strain) improves the interpretability of ecological patterns and the portability of findings across studies [6,7]. Methodological advances have progressively increased taxonomic resolution and reproducibility in amplicon workflows. Early pipelines grouped reads into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at fixed similarity thresholds, which simplified analysis but conflated biological and technical variation. However, these methods often fall short in delivering species-level resolution and are prone to variability across pipelines and datasets [8,9].

The shift toward exact sequence-based approaches (e.g., amplicon sequence variants, ASVs) reduced clustering artifacts for short-read data, improving comparability across experiments [10]. More recently, long-read sequencing has enabled recovery of near full-length 16S rRNA genes, potentially improving species-level assignment, disambiguating closely related taxa, and stabilizing ecological inferences in complex communities [11,12]. However, leveraging full-length reads requires algorithms that can accommodate read length–specific error structures, model multi-mapping to reference databases, and estimate abundances without overinflating diversity [13]. Emu, a taxonomic profiling method based on expectation-maximization (EM) to resolve ambiguous long-read mappings, yields compositional estimates that aim to be both accurate and robust for long-read 16S rRNA datasets [14].

Despite these advances, environmental microbiome studies still face challenges related to reproducibility and scale [5,15]. Reported community differences can be sensitive to choices in primer sets, reference databases, quality filters, and classification parameters, complicating meta-analysis and the accumulation of knowledge [8]. Soil and plant microbiomes also impose heavy computational demands due to complex experimental designs, due to high richness and the need for deeper sequencing to capture rare taxa, which can strain local computing resources [16]. High-performance computing (HPC) environments address scalability but are often perceived as inaccessible to new users and can themselves be sources of variability when software stacks, dependencies, or job-scheduling constraints differ across clusters [17,18]. For long-read 16S rRNA specifically, the lack of shared, domain-tailored, and fully documented workflows that integrate Emu with transparent quality control and benchmarking makes it difficult to evaluate performance across soil and plant compartments and to reproduce results across independent laboratories.

Consequently, there is a practical and conceptual gap: we lack a standardized, open, and reproducible long-read 16S rRNA pipeline that (i) is expressly designed for soil and plant microbiome questions, (ii) operationalizes best practices for quality control and reference-based inference with Emu, and (iii) scales predictably on HPC while producing portable, versioned outputs for downstream ecological analysis. Existing tutorials often target short-read OTU/ASV workflows or provide minimal guidance on how to tune long read–specific steps (e.g., length/quality screening, handling mapping, and database curation) under realistic environmental complexity [5,8,19]. Moreover, reproducibility guidance typically emphasizes containerization or environment capture but stops short of demonstrating that end-to-end results remain stable across different HPC clusters, settings, or modest updates to reference databases, factors that commonly change across institutional environments [15]. For interdisciplinary audiences, these limitations hinder the translation of microbiome insights into real practice interventions or ecological theory because conclusions may be contingent on opaque computational choices.

To address this need, a reproducible Emu-based workflow is presented for soil and plant microbiome profiling, designed for HPC execution while remaining accessible to users with varying computational backgrounds. The workflow is organized into four steps: long-read 16S rRNA gene input validation, quality control suited to full-length reads, reference-informed taxonomic assignment with Emu, and standardized outputs for ecological analyses, each accompanied by versioned configurations and human-readable reports. Reproducibility is supported through declarative configuration files so that identical inputs produce consistent outputs across different clusters, and scalability is demonstrated.

Software and datasets

The complete set of databases, software tools, and custom scripts required to reproduce this workflow is listed in Table 1, along with version numbers, access information, and licensing details. All custom scripts are available in the public GitHub repository and archived on Zenodo (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17764933; release v1.0.2).

Table 1. Databases, software, and custom scripts required to run the full Emu-based 16S microbiome workflow

| Type | Software/dataset/resource | Version | Date | License | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database | RefSeq (NCBI) Viridiplantae (mitochondria) | 1.1 | May, 2025 | Free | |

| Database | RefSeq (NCBI) Viridiplantae (plastid) | 3.1 | May, 2025 | Free | |

| Database | Emu prebuilt DB (OSF 56uf7) | v3.4.5 | May, 2023 | CC-BY | Free |

| Database | FAPROTAX database | v1.2.12 | May, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Software 1 | NanoPlot | 1.44.1 | June, 2023 | GPL-3.0 | Free |

| Software 2 | NanoStat | 1.6.0 | June, 2023 | GPL-3.0 | Free |

| Software 3 | NanoFilt | 2.8.0 | June, 2023 | GPL-3.0 | Free |

| Software 4 | Kraken2 | v.1.0 | July, 2025 | MIT | Free |

| Software 5 | Emu | v3.5.1 | January, 2021 | MIT | Free |

| Software 6 | R (base) | v4.4.2 | October, 2025 | GLP v2 | Free |

| Software 7 | Python | v3.8.0 | October, 2019 | BSD open source | Free |

| Script 1 | run_nanoplot_barcode.slurm | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 2 | run_nanofilt.slurm | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 3 | run_QC_summary.py | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 4 | download_plant_organelle_RefSeq_fastas.sh | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 5 | kraken2_add_build_db.slurm | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 6 | kraken2_classify_filter.slurm | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 7 | remove_kraken2_organelle_reads.py | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 8 | summarize_kraken2_reports.py | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 9 | run_emu.slurm | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 10 | collect_counts.py | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 11 | relab_to_counts.py | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 12 | downstream_microbiome.r | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 13 | emu-to-faprotax.py | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

| Script 14 | collapse_table.py | 10.5281/zenodo. 17764933; v1.0.2 | November, 2025 | CC-BY | Free |

Procedure

文章信息

稿件历史记录

提交日期: Sep 29, 2025

接收日期: Dec 7, 2025

在线发布日期: Jan 4, 2026

出版日期: Jan 20, 2026

版权信息

© 2026 The Author(s); This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

如何引用

Dias, H. M., Jain, R., Santos, V. A., Gonzalez-Hernandez, J. L., Solanki, S., Menendez III, H. M. and Graham, C. (2026). Reproducible Emu-Based Workflow for High-Fidelity Soil and Plant Microbiome Profiling on HPC Clusters. Bio-protocol 16(2): e5577. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.5577.

分类

生物信息学与计算生物学

微生物学 > 群落分析 > 宏基因组学

植物科学 > 植物免疫 > 宿主-细菌相互作用

您对这篇实验方法有问题吗?

在此处发布您的问题,我们将邀请本文作者来回答。同时,我们会将您的问题发布到Bio-protocol Exchange,以便寻求社区成员的帮助。

Share

Bluesky

X

Copy link